The land wears its rich past like an invisible cloak. Mystery and romance floats in the air; it seeps through the walls of the souks; and flows past the columns of its grand ruins. Syria’s classical ruins, bustling souks and dreamy mosques are from the pages of a One Thousand and One Arabian Nights fairy tale.

This was how I felt about Syria when I visited a few months before the crisis in Syria and before the uprising against President Assad turned into a civil war.

During my trip, I saw no signs of the crisis in Syria that would sweep through the country. Later, back home, I watched the news in horror at the fighting that would destroy the Syria I had the privilege of visiting.

Syria’s bloody past

For me, Syria had always been mysterious and exotic, an exciting desert country in the heart of the Middle East, bordering Turkey (to the north), Iraq (to the east), Israel and Jordan (to the south) and Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea (to the west).

I tingled with excitement as our bus left Tartus, where our ship, the MV Aegean Odyssey, had docked. As a keen student of art, history and culture of ancient civilisations,

I had chosen this cruise as a comfortable and informative way to explore the Mediterranean. One of the things that attracted me was the on-board lectures, which were delivered by highly qualified experts in ancient history. The knowledge I gained was several levels above the kind of information provided by a tour guide.

I discovered entire civilisations I’d never even heard of before and soaked up new knowledge about the Crusaders, Queen Zenobia and her desert kingdom of Palmyra, and Aleppo, which is a city that is possibly the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in the world.

As I travelled through Syria, each day, I felt like I was turning a page of a One Thousand and One Arabian Nights story. Even then, I knew that Syria had a bloody background. It’s a land where wars were fought and the blood of thousands split on the sand.

Will the crisis in Syria ever end?

The history of Syria is a tapestry of 5000 years of civilisations, from the Phoenicians, Assyrians and Persians, who were vanquished by Alexander the Great, to the Nabataeans, Romans and Crusaders.

It was part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuries before it fell to the French in 1920. Syria gained independence in 1946 but dreams of a “Greater Syria” were dashed when Britain and France formed Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan in the 1920s.

Even though I’ve only visited Syria once, I’m greatly disturbed to learn that thousands of historic sites in Syria have been vandalised, looted and destroyed by war. Syria’s World Heritage sites were as impressive as any I’ve seen. Yet, even before the civil war, few people, aside from archaeologists, had laid eyes on them.

I visited three of the country’s five World Heritage sites: Krak des Chevaliers, a once impressive Crusader castle, the ancient city of Aleppo and Syria’s World Heritage star, Palmyra.

Krak des Chevaliers

Krak des Chevaliers is located above the village of Ma’alula where Aramaic, Jesus’s mother tongue, is spoken. The sloping cobblestone ramp was wide enough for chariots to ride through.

It swept past a guard room, stables and into the moat area. Exploring its halls, courtyards and tunnels reminded me of scenes from the movie Kingdom of Heaven.

Looking at the photos of the castle now, you’d hardly believe that Krak des Chevaliers was the world’s best preserved Crusader Castle before it was bombed in March 2014.

The castles strategic location – in the corridor between Syria’s interior and the coast at the entrance to Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley – guaranteed it would be a fiercely contested location in this war, just as it was during the Crusade. Only this time, the world has missiles and bombs.

Palmyra

From the castle, we continued our journey past tomato and aubergine farms, and apricot, almond and apple orchards.

Trucks piled high with vegetables and lorries transporting goods from Tartus to Iraq whooshed past. Then the land opened up into flat desert plains and my eyes adjusted to the blur of ochre landscape whipping past my window.

We arrived at Syria’s World Heritage attraction, Palmyra, an oasis about 250km from Tartus and 215km from Damascus at sunset.

It was a magical time of the day. Grand colonnaded ruins and temples devoted to Mesopotamian gods were bathed in golden light. Looking at the ancient structures in the soft light made my heart bloom with the anticipation of exploring these ruins.

We rolled past luxury hotels and the Prince of Qatar’s private villa, built for the royal visitor to stay in while attending camel races.

Built by the Romans, Palmyra was a great desert city and a bustling trading post for caravans carrying silk, spices, dates and slaves between Arabia, Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean. Except for friezes, statues and ancient utensils, much was left to your imagination but there was enough to entice my mind.

When I visited, what was left of the once-bustling trading hub was a one-street town with an eclectic assortment of shops. I wandered into a camel leather sandal maker’s shop and scarf shops. My favourites were the curio shops packed with an assortment of old wares, such as suits of dented armour, rusty coins, clocks and Bedouin knives.

Back at the Dedeman Hotel, which was one of several luxury hotels in town, I remember ordering a nip of Syrian arak at the bar, then after dinner, retiring to my verandah to gaze at views across the swimming pool to the medieval Arab citadel of Qala’at ibn Maan, a 17th-century castle built by a Lebanese warlord and ponder the life of Queen Zenobia.

I was not to know that Syrian armed forces would set up base in the citadel. According to BBC News, shells fired from the citadel has caused damage to the ancient site.

Queen Zenobia gathered an army and surged through Syria, Palestine and part of Egypt, conquering 1/3 of the Roman Empire before the Romans got the better of her.

She was captured and paraded through the streets of Rome in golden chains. It was the beginning of the end for Palmyra’s golden days.

During the recent civil war, shells have hit the columns of the Temple of Bel causing two of them to collapse. And the army has dug a road and earth dykes and installed multiple rocket launchers inside the camp of the emperor Diocletian.

While Palmyra was vast and grand, the ancient city of Aleppo was full of nooks and bristling with character. Aleppo was the capital of Yamhad, a powerful kingdom of the Middle East from the middle to late Bronze Age. It is believed to have been inhabited continuously for 8000 years.

Aleppo

Aleppo’s Great Mosque, founded in the early 8th Century, came under heavy fire. The minaret has collapse and there are large craters.

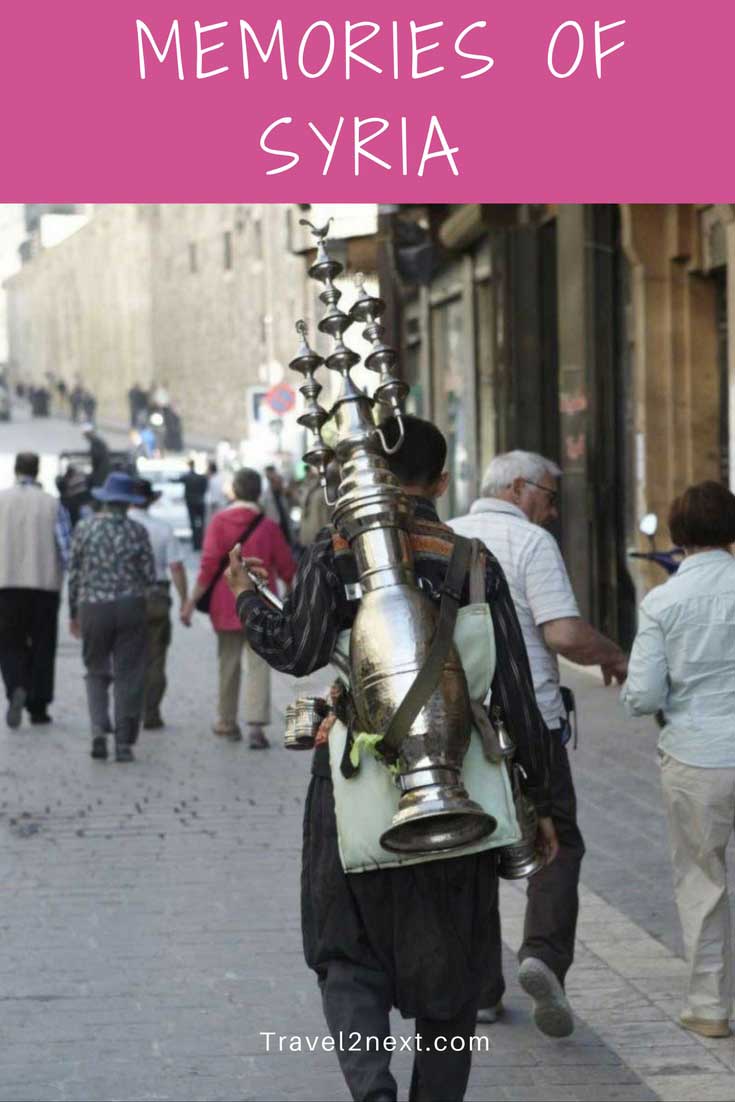

Visiting Syria’s historic sites is awe-inspiring but it’s the spontaneous experiences that such as haggling over a carpet with Mahmoud, a persistent Bedouin, in Palmyra, and photographing a man smoking a shisha pipe in a café and being surprised when he whipped out a camera to snap a photograph of me.

I plunged into the labyrinth of Aleppo’s souk, marvelling at the maze of narrow lanes brushing past young boys pushing wagons of sweets through the crowd, housewives stocking up on nuts, spices and meat and women shopping for perfume and scarves. Aleppo’s souks date back to the 13th Century and were the heart of the city’s commercial activities. I found the main souk both enticing and confusing.

There were mounds of frilly rainbow-coloured cotton bras displayed alongside shops selling hijabs, the shapeless coats of the devout.

At one shop, a man puffed on a pipe as I fingered feather-light silk scarves in rainbow colours. He stopped puffing when he learnt I lived in Australia.

“My uncle lives in Sydney,” he said.

Aware of the local tendency to claim a family connection with visitors to strike up rapport, I didn’t believe him.

I pointed at the cardboard sign advertising the scarves at 600 Syrian pounds each ($12).

His uncle – hefty man called Aladdin – suddenly appeared and greeted me like a long-lost friend. He whipped out his New South Wales driver’s licence to prove our connection.

He told me he was visiting Syria for a year to help with the family business.

I left his stall with silk scarves for all my friends and a promise to return one day. It saddens me to say that I don’t know if I will ever be able to keep that promise.

I was horrified to learn that Free Syrian Army rebels established a headquarters in a bath-house near the old souk. The souk became a target and during the shelling an electricity sub-station caught fire. Flames quickly spread and burnt the souk’s wooden doors and wares to ash.

Do you believe the crisis in Syria will come to an end soon?

The Australia government strongly advises Australians not to travel to Syria because of the extremely dangerous security situation, highlighted by ongoing military conflict including aerial bombardment, kidnappings and terrorist attacks. The Australian Government has recommended, since April 2011, that Australians in Syria depart immediately by commercial means while it is possible to do so.

Discover Middle East

Lost City of Petra

Jordan tourism – Land of milk and honey

Aleppo (October 2010) before Arab Spring

Plan Your Trip

Rent A Car – Find the best car rental rates at Discover Cars. They compare car hire companies to provide you with the best deal right now.

Find A Hotel – If you’re curious about this article and are looking for somewhere to stay, take a look at these amazing hotels.